Wi-Fi Roaming Performance in MDUs: Navigating Seamless Connectivity

Introduction: The Quest for Uninterrupted Connectivity

At 802.11 Networks Corp, we’re driven by a passion for Enterprise Wireless. We believe in demystifying complex topics, diving deep into the technical intricacies, and presenting our findings in a way that sparks conversation and propels industry-wide improvements. Today, we’re focusing on a critical aspect of modern living: Wi-Fi roaming in Multi-Dwelling Units (MDUs).

Think bustling apartment complexes, vibrant student housing, comfortable senior living facilities, and modern condominiums. Why this focus?

- Ubiquity of MDU Living: A significant portion of the population resides in MDUs. In the US, estimates range from 30% to 42%, highlighting the sheer scale of this living arrangement.

- The Promise of Managed Wi-Fi: MDUs offer a unique opportunity for property-wide, managed Wi-Fi solutions. When implemented effectively, these systems deliver substantial technical and economic advantages to residents.

A cornerstone of a successful managed Wi-Fi deployment is seamless roaming. Residents expect their connected devices to transition smoothly between access points (APs) as they move throughout the property. This eliminates frustrating disconnections and ensures a consistent user experience.

In this post, we’ll dissect common MDU deployment architectures, exploring their strengths and weaknesses. We’ll start by differentiating between managed and non-managed environments, then delve into four specific client authentication and roaming scenarios. Our goal is not to declare a “winner” but to foster a constructive dialogue that enhances human connectivity.

Understanding MDU Wi-Fi Architectures

To fully understand the results of the performance test, we must first understand the architectures that are being tested.

1. Traditional Residential Deployments: The “Home Router” Approach

- Each apartment operates its own dedicated home router.

- These networks typically feature:

- A private SSID secured with WPA2-Personal for individual residents.

- A universal SSID, often utilizing Passpoint with pre-installed profiles, enabling limited roaming across the complex.

- Technical Characteristics:

- NAT (Network Address Translation) is standard, isolating each apartment’s network.

- 802.11r (Fast Transition) is generally absent.

- Some APs may implement key caching to expedite re-authentication for returning devices.

- Limitations:

- Limited roaming performance.

- Interference between many routers.

- Difficult to manage as a whole.

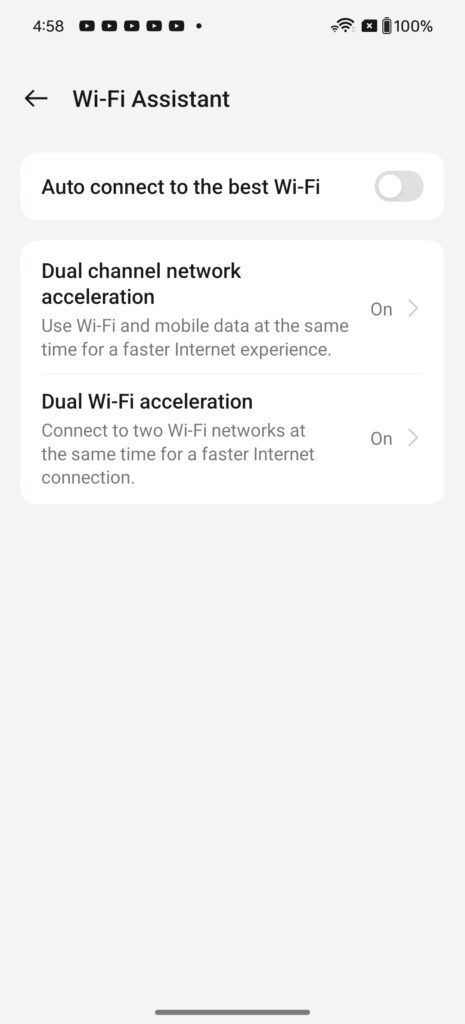

2. Managed MDU Deployments: Centralized Control

- A professionally designed RF network covers the entire property.

- APs are strategically placed based on a thorough RF survey, ensuring optimal coverage.

- A single, unified SSID is broadcast throughout the property.

- Technical Characteristics:

- VLANs (Virtual Local Area Networks) are employed to segregate resident traffic, ensuring privacy and security.

- Authentication options include:

- Passpoint-like systems with pre-installed profiles (ideal for smartphones and laptops).

- Multi-PSK (MPSK) solutions with RADIUS authentication (offering a balance of security and ease of use, and better IoT compatibility).

- Key Points:

- Allows 802.11r to be implemented

- Centralized management and troubleshooting.

- Enhanced security and privacy relative to using a single, shared PSK.

- Ability to fine tune the network.

Quantifying Roaming Performance: The Test Bed

To objectively assess roaming performance, we constructed a test bed that replicated the scenarios described above. We distilled the myriad of possible configurations into four representative cases:

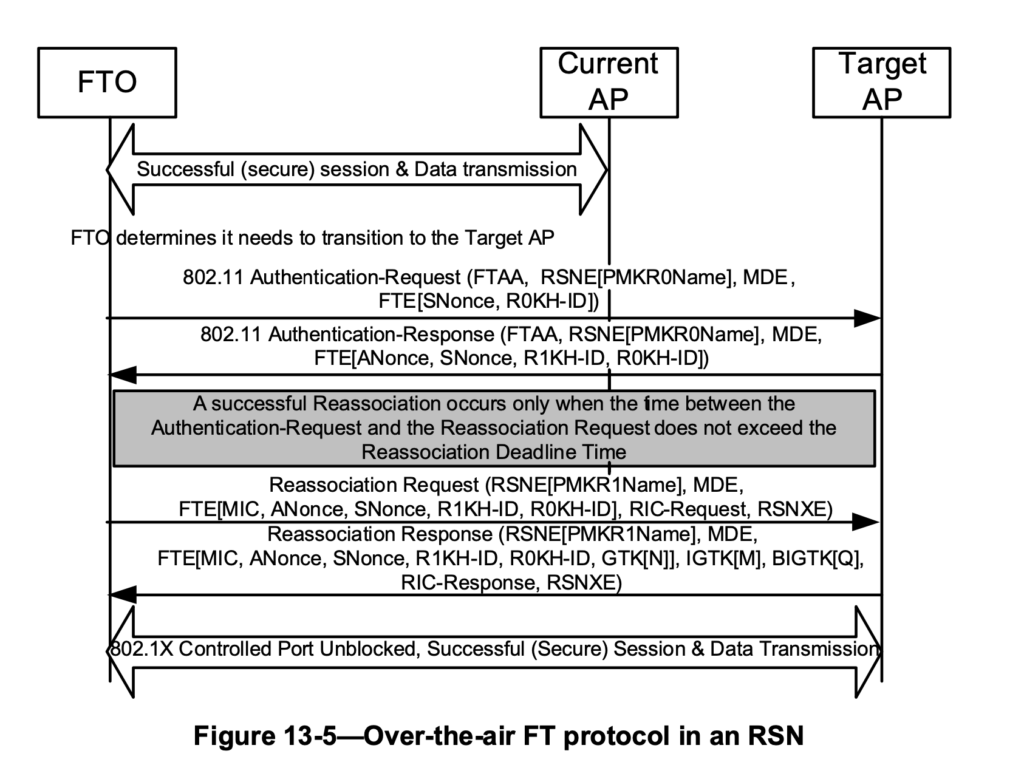

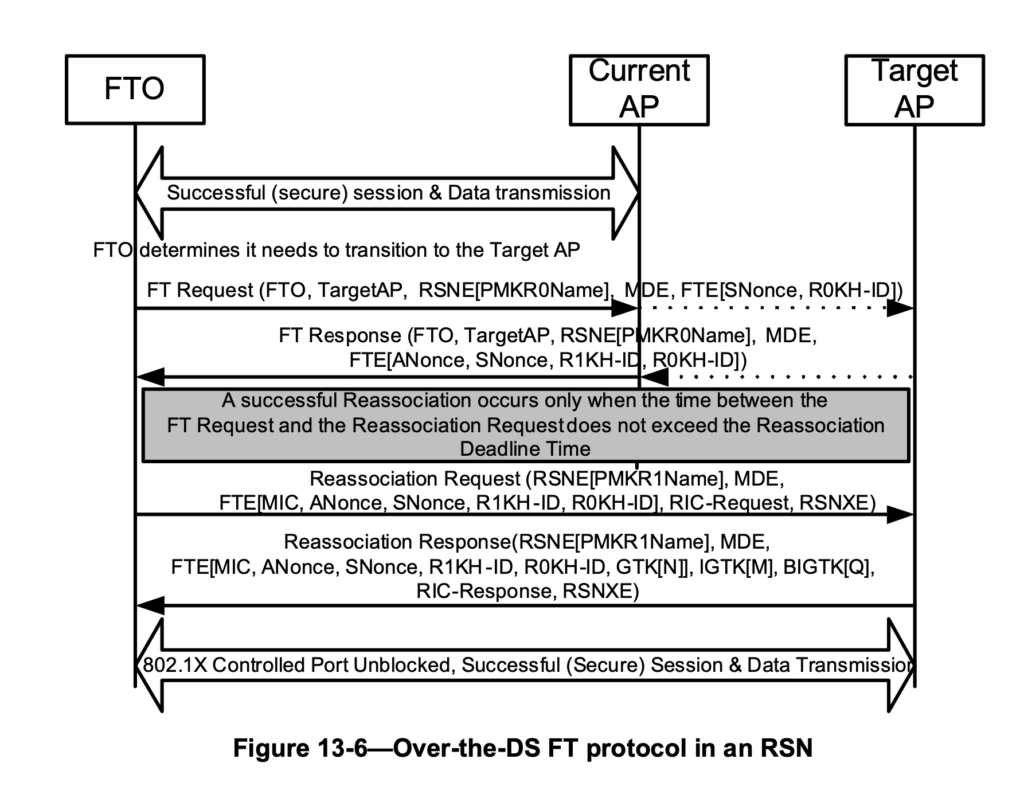

- WPA2-Enterprise (TLS) + Bridged + 802.11r:

- Represents a managed MDU with Passpoint or similar pre-installed profiles.

- Bridged network: Clients retain their IP address during roaming.

- 802.11r: Rapid authentication using R1 keys distributed via the Distribution System (DS).

- WPA2-Enterprise (TLS) + NAT’d + Key-Caching:

- Mirrors the universal roaming SSID in traditional residential deployments (e.g., Xfinity Mobile Hotspot).

- NAT’d network: DHCP lease renewal and Layer 3 (L3) connection break during roaming.

- Key caching: Speeds up re-authentication for returning clients, but no 802.11r.

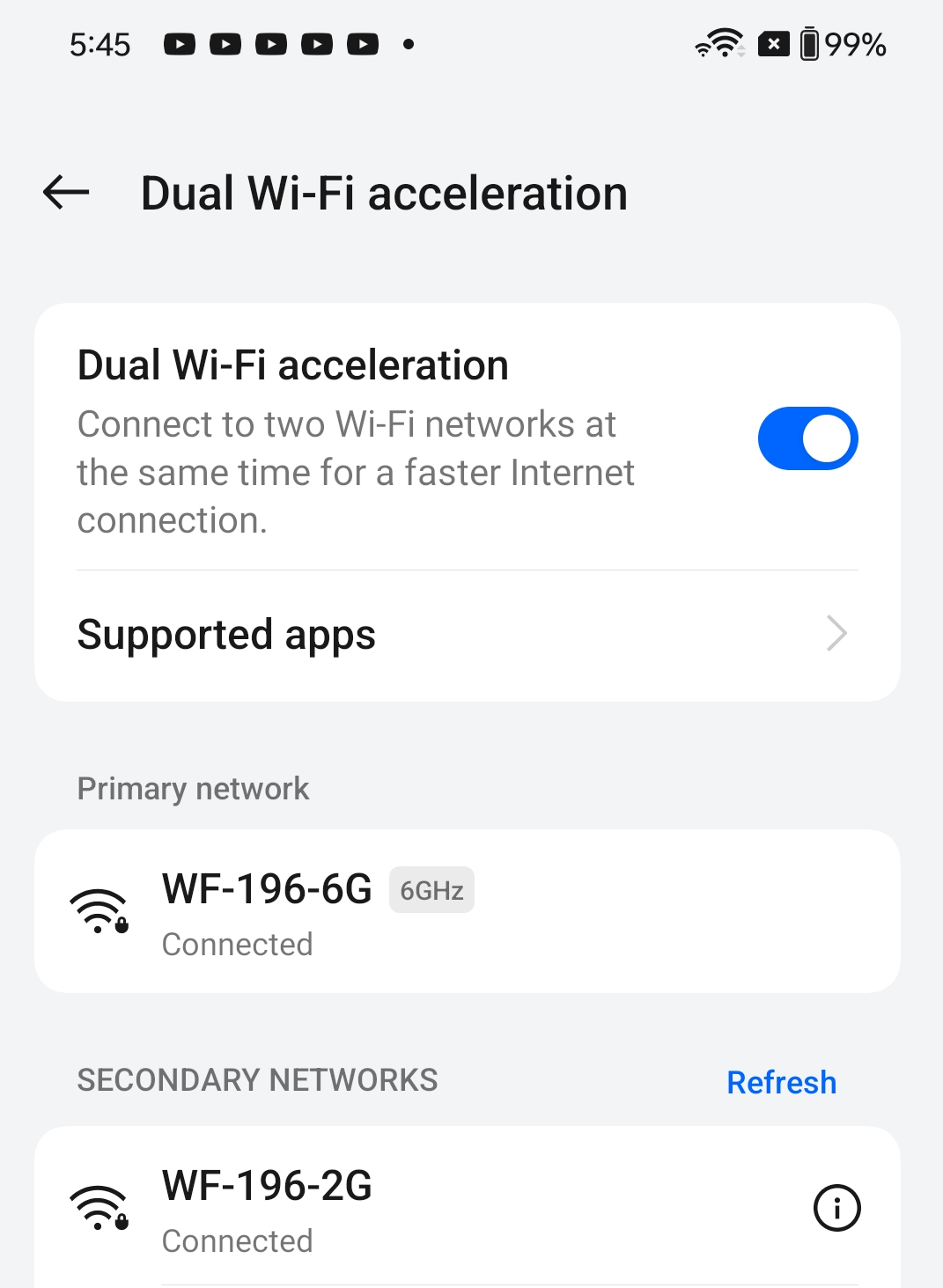

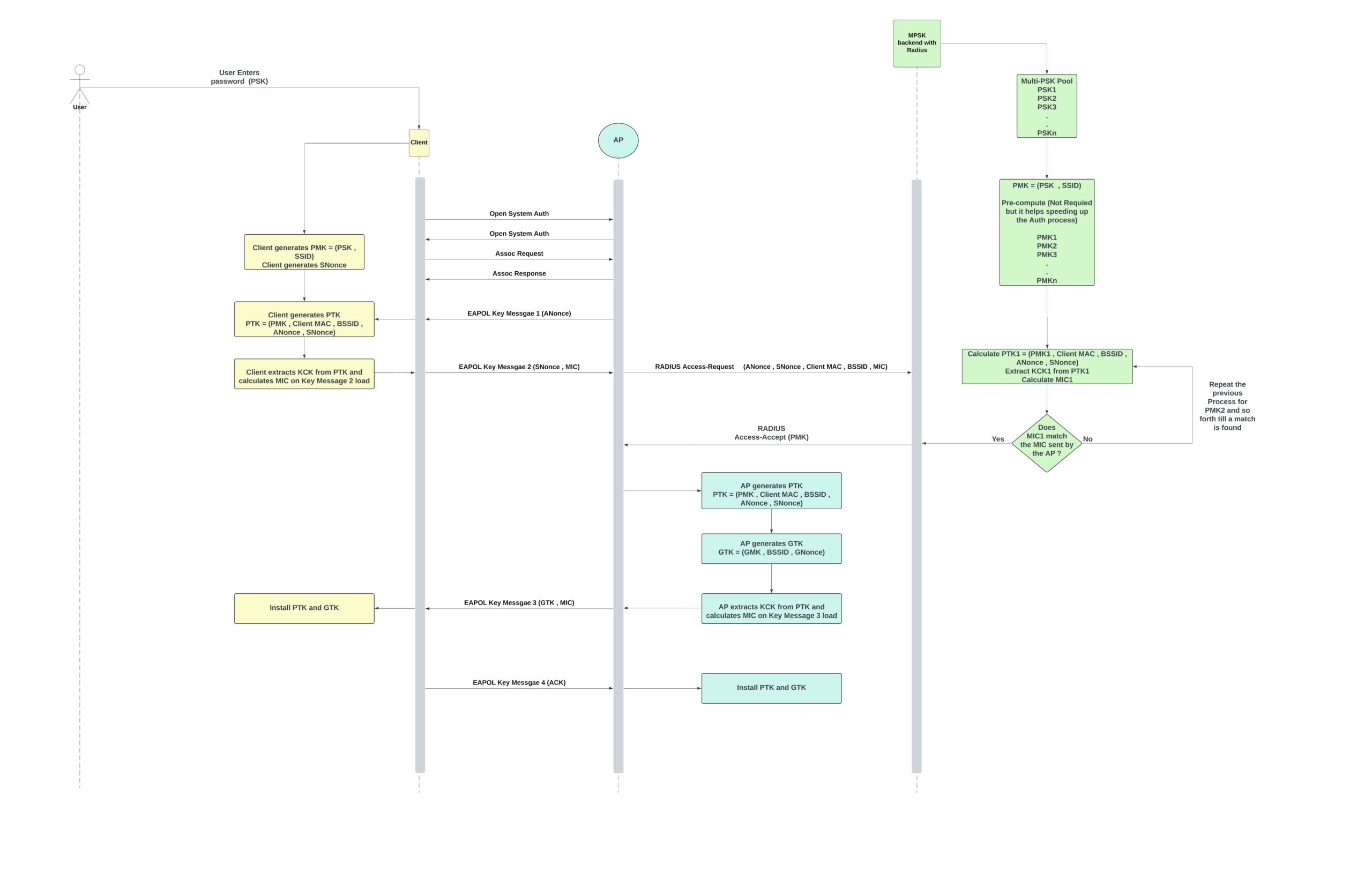

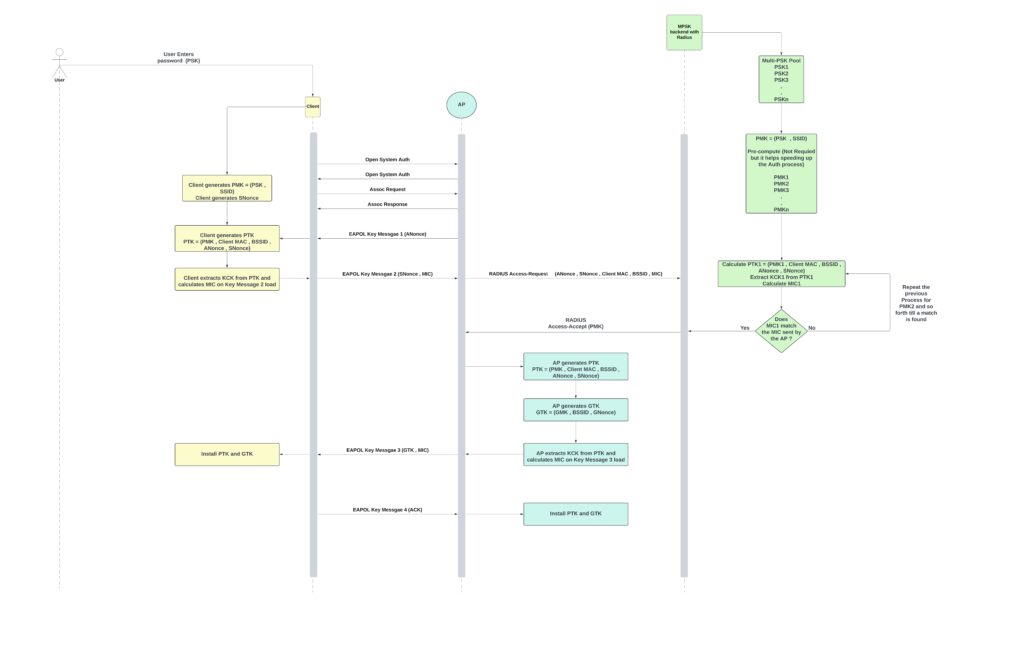

- MPSK-RADIUS + Bridged + 802.11r (or Key-Caching):

- Represents a managed MDU with MPSK and RADIUS authentication.

- Bridged network: Maintains L3 connection.

- 802.11r availability based on capabilities of backend MPSK solution used

- Each resident gets a unique PSK tied to a VLAN.

- MPSK-RADIUS + NAT’d + Key-Caching:

- While less common, it was tested to provide a complete view.

- NAT’d network.

- Key Caching.

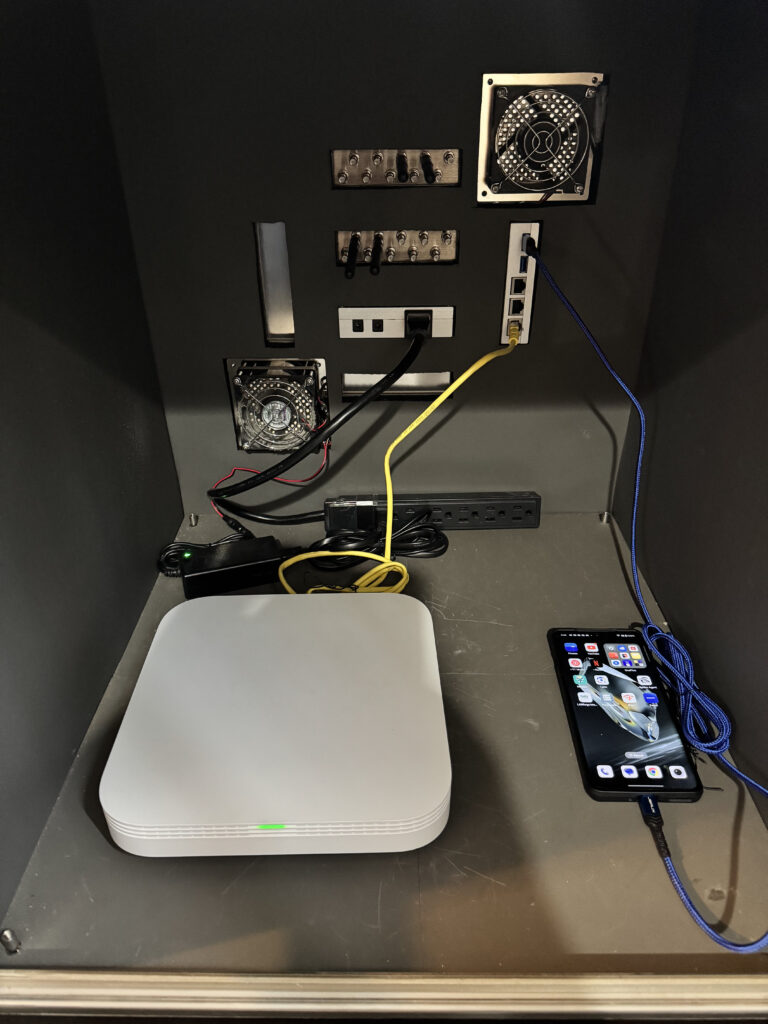

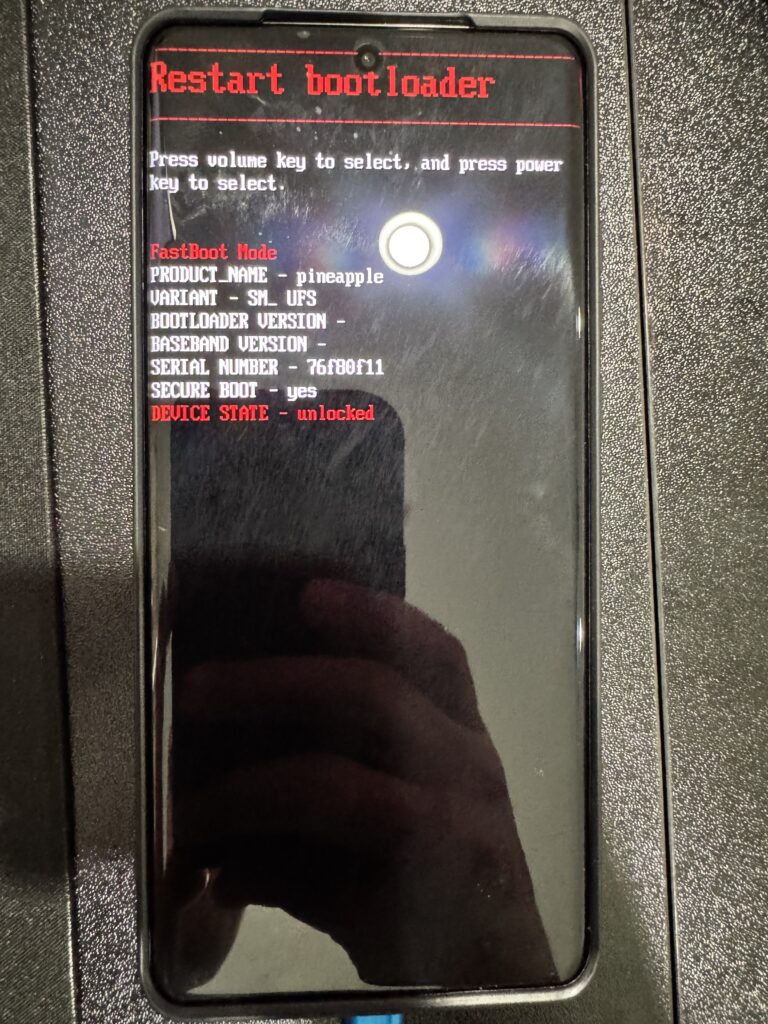

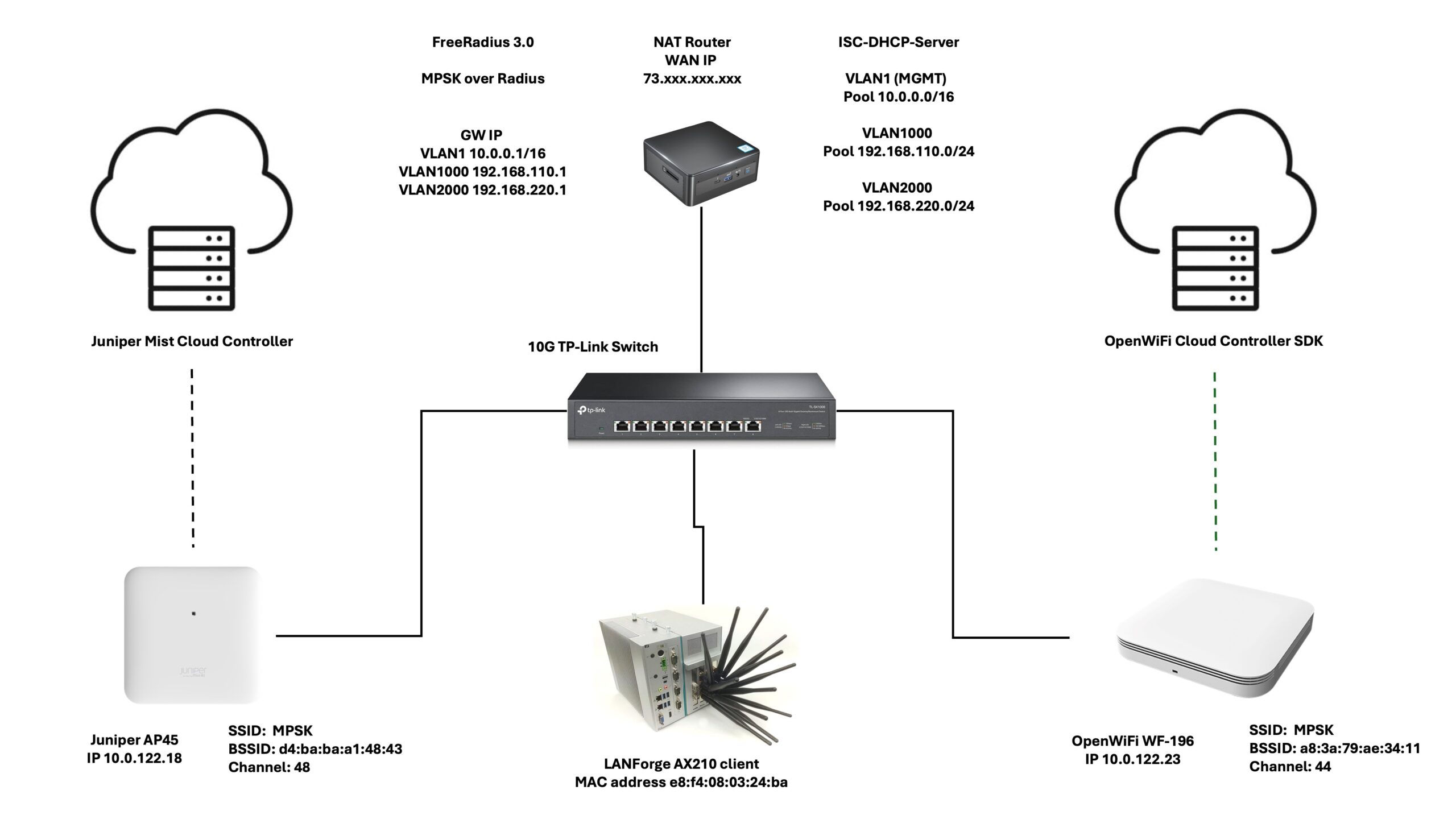

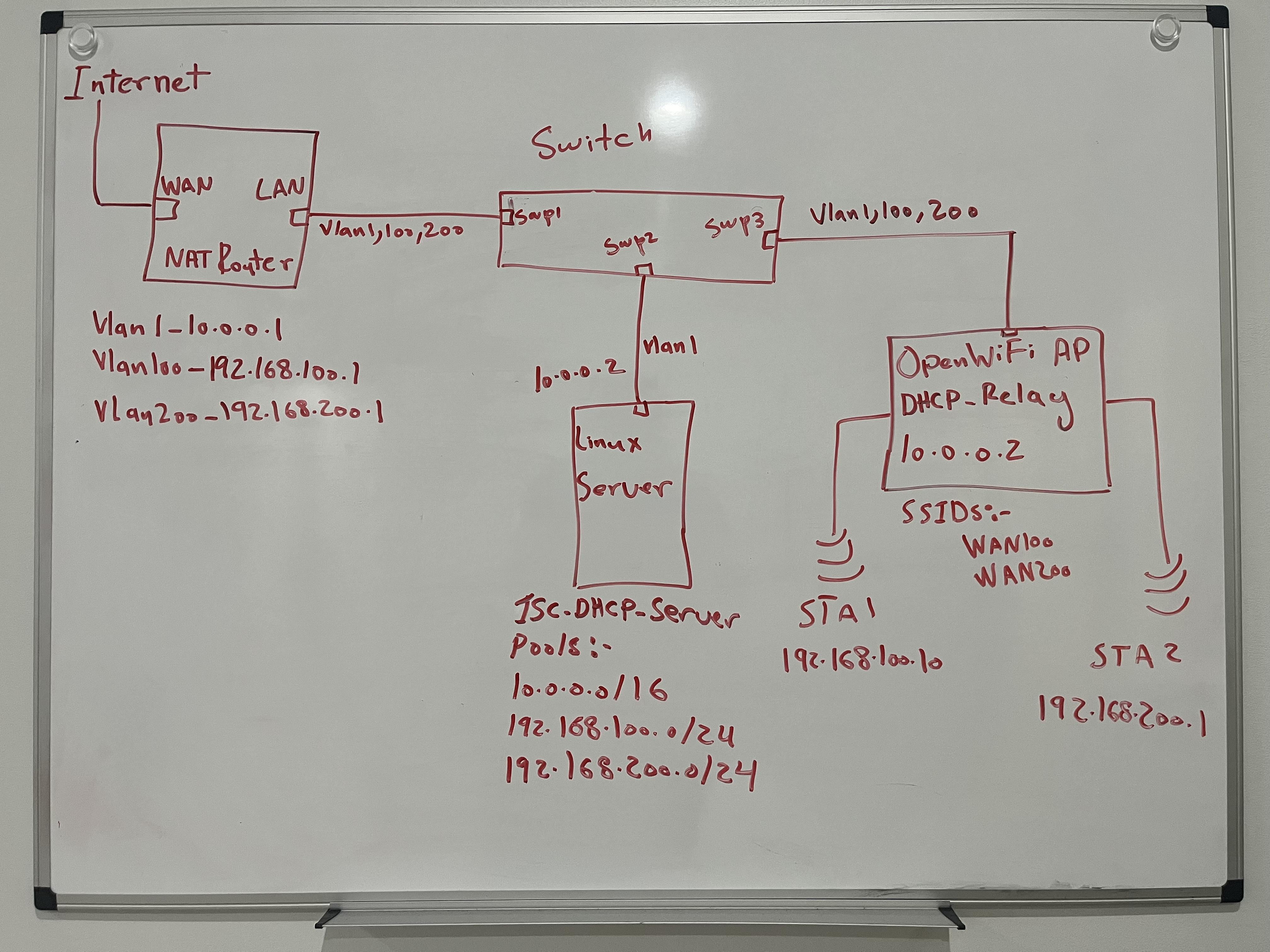

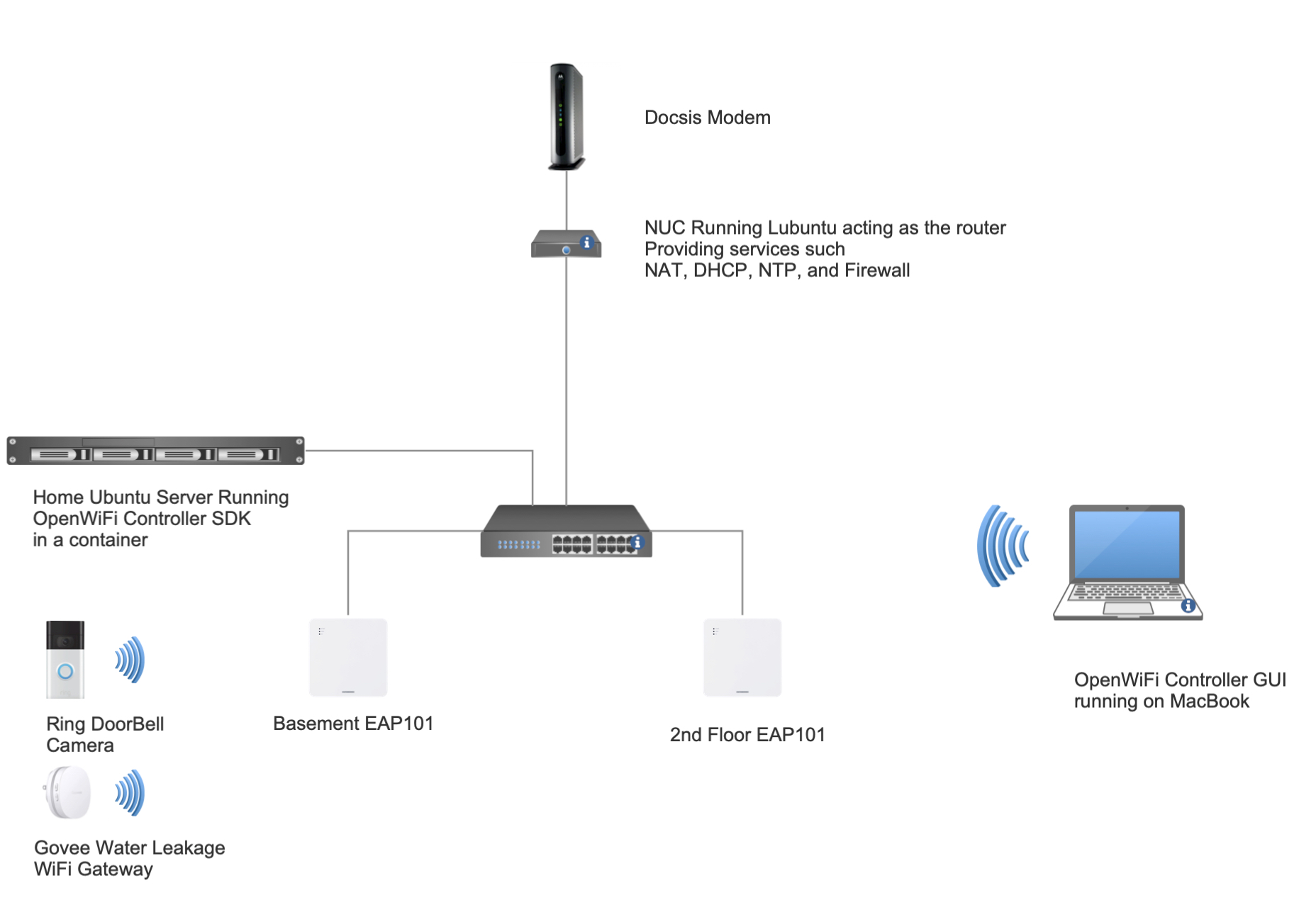

The Test Setup: Precision and Control

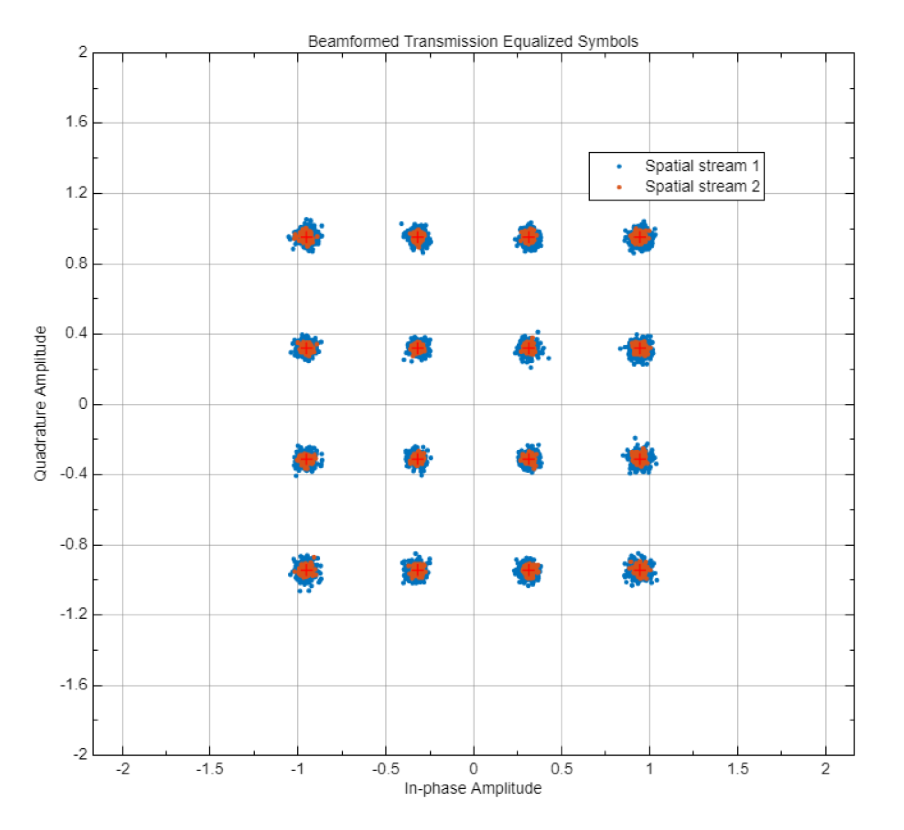

- Two Enterprise OpenWiFi APs broadcasted the four SSIDs, each corresponding to a test case.

- The APs were connected to a Linux-based router (providing DHCP, RADIUS, and NAT) via a switch.

- FreeRADIUS was used for RADIUS authentication.

- All tests were conducted in RF isolation chambers to ensure accuracy.

- Roaming events were manually triggered for consistent results.

Test Architecture Diagram:

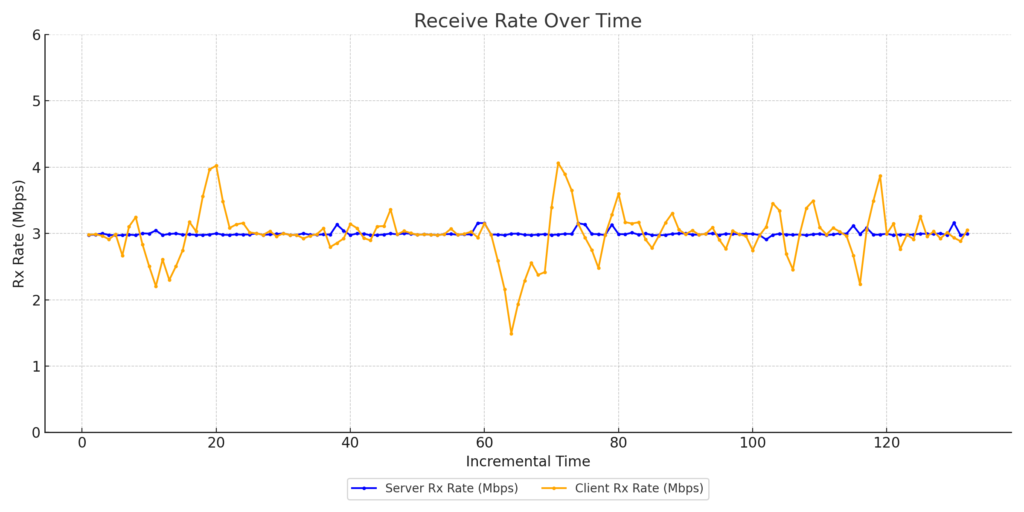

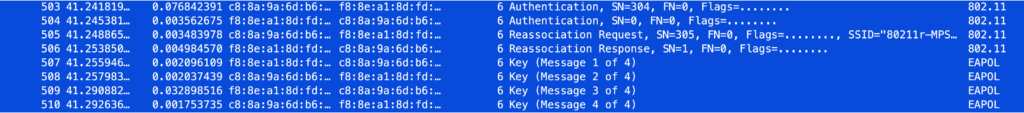

Test Execution: Measuring Roaming Dynamics

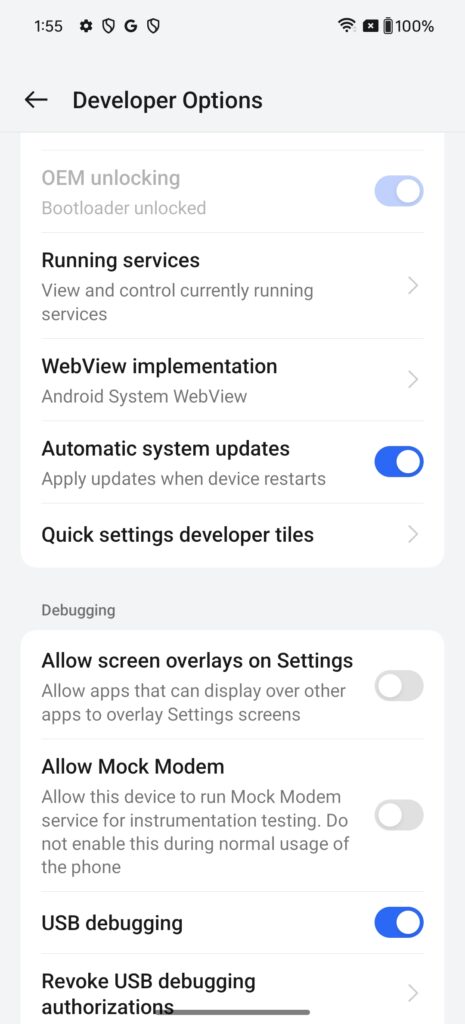

- Each test began with a pre-authenticated client connected to AP1.

- A continuous ping to 8.8.8.8 (Google DNS) was executed with a 1-second interval.

- Four manual roaming events were triggered during the 100-ping test.

- Latency and packet loss were recorded for each scenario.

Results: A Clear Picture of Performance

- WPA2-Enterprise (TLS) + Bridged + 802.11r:

- Packet Loss: 4%

- Average Latency: 16.98 ms

- WPA2-Enterprise (TLS) + NAT’d + Key-Caching:

- Packet Loss: 12%

- Average Latency: 19.91 ms

- MPSK-RADIUS + Bridged + 802.11r:

- Packet Loss: 1%

- Average Latency: 18.20 ms

- MPSK-RADIUS + NAT’d + Key-Caching:

- Packet Loss: 9%

- Average Latency: 18.07 ms

Analysis and Conclusion: Optimizing MDU Wi-Fi

Why Roaming Matters: Seamless roaming is essential for a positive user experience in MDUs. Disruptions lead to frustration and decreased productivity.

Best Solutions:

- Managed MDUs:

- Regardless of the authentication method (MPSK/WPA2-Enterprise), Bridged networks with 802.11r offer excellent performance.

- MPSK-RADIUS with VLANs adds user-friendlinesss for IoT devices

- Traditional Residential:

- NAT’d networks with key caching are common, but less ideal.

- Requires separate, universal SSID for Roaming across property.

Client Considerations:

- Passpoint benefits devices with pre-installed profiles.

- MPSK-RADIUS accommodates IoT and other devices with limited capabilities.

Comparison Matrix:

| Feature | WPA2-Enterprise (TLS) + Bridged + 802.11r | WPA2-Enterprise (TLS) + NAT’d + Key-Caching | MPSK-RADIUS + Bridged + 802.11r | MPSK-RADIUS + NAT’d + Key-Caching |

| Network Mode | Bridged | NAT’d | Bridged | NAT’d |

| Roaming Support | 802.11r | Key-Caching | 802.11r (partial) | Key-Caching |

| Authentication | Passpoint (pre-installed profiles) | Passpoint (pre-installed profiles) | MPSK | MPSK |

| Traffic Segmentation | VLANs | Per-user NAT | VLANs | Per-user NAT |

| Packet Loss | 4% | 12% | 1% | 9% |

| Average Latency (ms) | 16.98 | 19.91 | 18.20 | 18.07 |

| Best Use Case | Managed MDU, devices with Passpoint profiles | Traditional Residential Model (Separate NAT’d Home Router per unit) | Managed MDU, diverse client device types | Less Common deployment use cases. TBD. |

| Pros | Lowest latency, seamless roaming | Simpler NAT isolation | Very low packet loss, diverse client ecosystem | TBD |

| Cons | Passpoint reliance can limit IoT device support | Higher packet loss, DHCP renewals | Partial 802.11r support | Higher packet loss compared to Bridged 802.11r |

Key Takeaway: By understanding these technical nuances, Professional WLAN experts, like 802.11 Networks Corp, can help ISPs & MDU Network Operators to deliver exceptional roaming experiences.